It’s hardly surprising

that the UK National Minimum Wage (NMW) has become a hot political topic again

given the historically unprecedented fall in real wages which followed the

2008/09 recession; a decline that is still ongoing for many if not most workers.

Indeed, as concern grows

over falling wage shares and rising inequality, minimum wages are the subject

of lively debate in countries across the globe: Germany is on the cusp of

introducing a minimum wage, Swiss voters have just rejected a relatively high minimum wage and some fascinating developments are taking

place at state and metropolitan level across the US.

The degree of political

support now associated with the UK NMW is quite remarkable; not only are the

Labour Party and SNP bringing forward proposals to boost the value of the NMW,

even George Osborne is talking up significant real terms increases. In such

circumstances it’s easy to forget the ferocity of the opposition to its introduction

back in 1999.

But what exactly do our

political parties propose to do about the minimum wage? Earlier this week the

Labour Party published “Low Pay: the Nation’s Challenge”, a report prepared by

ex-KPMG honcho Alan Buckle. The report - the recommendations of which are strikingly similar to those in a recent Resolution Foundation report - proposes a number of measures to boost the

minimum wage relative to median earnings:

- Introducing a five-year target to increase the minimum wage to a more stretching (unspecified) proportion of median earnings. A degree of flexibility is retained in the framework: if due to changing economic circumstances the Low Pay Commission (LPC) believes the target cannot be met, they must write to the Secretary of State setting out their reasons. The burden of proof will fall on the LPC whereas in the current system it lies with the Secretary of State if he/she chooses to contest the LPC’s recommendation;

- Empowering the LPC to establish taskforces of key stakeholders in low pay sectors that are identified as having the potential to pay higher wages with the potential of setting a higher recommended or statutory rate for the sector;

- Changing the remit of the LPC to give it a stronger role with a longer-term focus – implicit in the above recommendations;

- Improving enforcement;

- Introducing a number of measures to ‘encourage’ employers to pay a Living Wage: procurement, tax incentives etc.

“…a firm

commitment that if we are the government in an independent Scotland, the

minimum wage will in future rise at least in line with inflation.

“This Scottish Government's Fair Work Commission [which will replace the

LPC in an independent Scotland], with

members drawn from business, trade unions and wider society, will advise the

government on the minimum wage. The Commission will also provide advice on

other factors relating to individual and collective rights which contribute to

fairness at work and business competitiveness, recognising that both are

integral elements of sustainable economic growth in Scotland. The Commission

will work with the larger Convention on Employment and Labour Relations.

Together they will help the Scottish Government foster a constructive and

collaborative approach to industrial relations policy and formalise the

relationship between government, employers, trade unions and employee

associations”.

It’s reasonable to expect the relative

merits of these proposals to come under some scrutiny in the run up to the

referendum. Is the best approach to index the NMW to inflation or

median wage?

Maybe neither for since its introduction in 1999 the NMW has comfortably outstripped

both wages (average and median) and inflation:

But the real

value of the NMW has fallen since the recession (although it has maintained its strength relative to the median gross

hourly wage - 54.6% in 2013 - because of the historic decline in median earnings) and it's important that politicians urgently consider ways in which it might be restored. For me it is the Resolution Foundation's approach which is most persuasive; a broader approach to the issue of low pay is essential and overdue.The Government should make an explicit long-term commitment to reducing the incidence of low pay and it should resource the LPC appropriately.

The Buckle Report recognises that the

LPC is effective and credible as the Scottish Government tacitly

acknowledges in proposing a Scottish version – the Fair Work Commission. Yet the proposals of both would constrain its flexibility.

This is particularly interesting in the

case of the Scottish Government since the whole approach to industrial

relations and labour market policy set out in the White Paper is based around the concept of

social partnership. The LPC is one of the UK’s very few social

partnership institutions. If the Scottish Government is genuinely committed to

the concept then why not let the social partners get on and do their job?

Of course regulatory

responses to a NMW declining in real terms and a falling wage share in general have their

limits. Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland don’t have a national minimum wage. But they all have very high rates of trade union density:

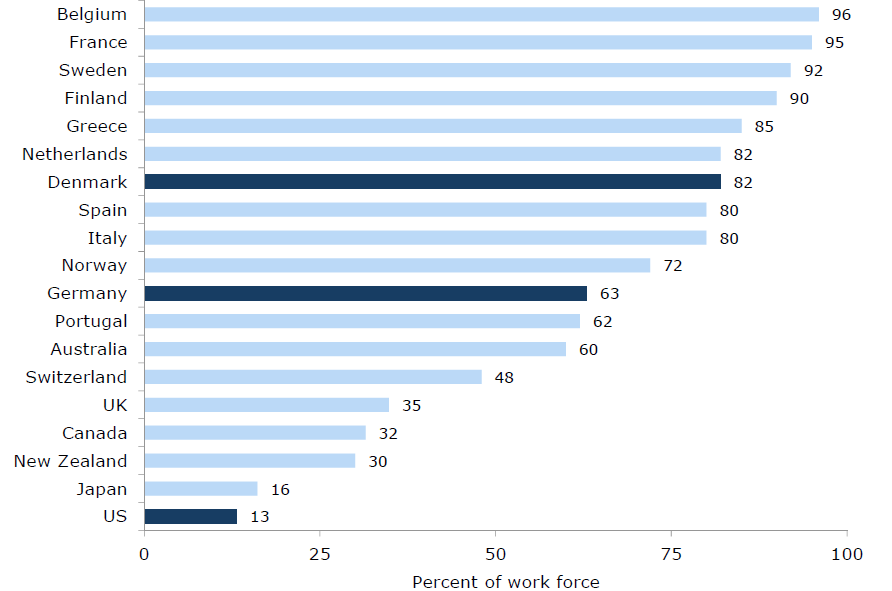

...and collective bargaining coverage (2007):

...and higher wages and total labour costs:

(Source: Eurostat, hourly labour costs

(wages and salaries and non-wage costs such as employers’ social contributions)

in EU 28, March 2014)

...and lower incidence of low wage work:

It’s no accident that the UK national

minimum wage (NMW) was introduced in 1999 following a steep and sustained decline in union

membership:

Replicating Nordic rates of TU density and collective bargaining coverage is a long-term and difficult project under any constitutional scenario. Nevertheless, it would be nice if politicians concerned about low pay could strongly and explicitly acknowledge that ‘collective bargaining is a more efficient way of protecting workers than the law’. A genuine commitment to boosting wages at the bottom end of the income distribution needs to be accompanied by a willingness to confront the asymmetries of economic power which run through Scotland's economy. Examining the role Government might reasonably play in boosting

union membership and collective bargaining coverage looks like a good place to start.

Stephen Boyd - STUC

Stephen Boyd - STUC