The latest

labour market statistics for Scotland (see table HI11)) published

on 17 April were undoubtedly the most positive for some months: unemployment

fell (slightly), employment rose (considerably) and inactivity fell (slightly). At FMQs the following day, the First Minister quite properly emphasized the good news, taking care to stress that ‘over the last year youth unemployment has declined by a third’.

Given that total

unemployment has fallen by only 10% over the same period, the decline in youth unemployment would indeed be

remarkable if accurate. But is it? Well, not unusually for labour market

statistics, the picture is somewhat complex...

The claim that youth

unemployment fell by a third in Scotland over the past year is based on

statistics published separately from the headline employment, unemployment and

activity statistics that usually determine the course of political debate.

These figures do indeed show Scotland outperforming the rest of the UK to a

significant degree (albeit that a fall of 31% doesn’t quite meet the stretching

technical definition of ‘one third’!):

Before anyone is

tempted to scream foul, it should be noted that the designation ‘experimental’

doesn’t necessarily render the statistics invalid. ONS concerns may well relate

to other nations/regions of the UK with a smaller sample size than Scotland.

OK, so let’s assume

that the Scottish statistics are correct. They should at least broadly align

with other measures of unemployment; measures that the Scottish Government’s

own briefings confirm as more reliable than the experimental LFS figures.

The Scottish

Government’s youth unemployment statistical briefings present the experimental

LFS data accompanied by data drawn from the Annual Population Survey which it informs

us is ‘based on a larger sample than the

quarterly LFS information and provides a more reliable estimate of economic

activity by age for Scotland’. What do APS data show? An encouraging fall

in youth unemployment but well short of the one-third claimed by the FM and

much more in line with the total fall in unemployment (all ages) over this

period:

The following chart

is derived from the Scottish Government’s latest briefing (April 2013 - see previous link) and shows the change in

the APS and experimental LFS rates over the latest year for which data are

available:

Clearly the performance

of this cohort is much less impressive on the APS measure: a much smaller fall

in unemployment, a fall in employment and a significant rise in inactivity. Again,

this performance is much more in line with the labour market as a whole.

However, the APS data lags the LFS data – so perhaps a big fall in youth

unemployment occurred at the start of 2013?

If so, it’s

reasonable to expect that this would be reflected to at least some extent in

the claimant count (JSA) which is the most up to date and reliable measure

(although obviously narrower as it only includes those on JSA – LFS and APS

includes all those unemployed, seeking and able to start, work) given that it

is drawn directly from the Jobcentre Plus administrative system. What’s

happening in the claimant count?

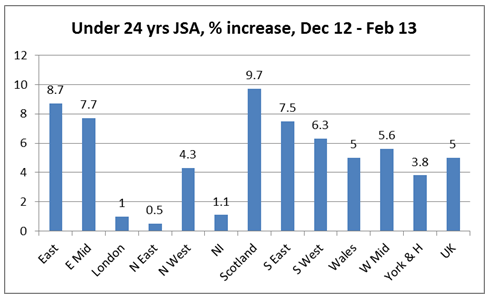

JSA is actually

increasing over the recent period and Scotland has seen a bigger increase than

any other nation/region of the UK. However, the latest month for which we

have figures seen all nations/regions of the UK experience a fall in youth JSA –

Scotland’s fall is below the average for the UK but not by a huge margin - but

not of a sufficient scale to see a return even to late 2012 levels:

It’s definitely

worth stressing that over the year youth JSA has seen an encouraging fall but, again,

this is much more in line with the APS youth data and total fall in unemployment than it is with the

experimental LFS data:

It might also be

helpful to look more closely at how the experimental LFS data tracks the rest

of the labour market. The following graph shows the change in the headline LFS

unemployment rate for all workers (16yrs and over) and the rate for the experimental data for 16-24yr

olds; the disparity is particulary marked in some nations/regions including Scotland:

One other area

deserves further examination: the 16-24 experimental figures are broken down

into 16/17 yr olds and 18-24 year olds. The trends for the two cohorts could

hardly be more different over the last year. Scotland has performed

exceptionally well on the 18-24 measure; witnessing a massive fall in

unemployment of 43.7%:

However the opposite

is true for 16 & 17 year olds for whom the increase in unemployment has

been much, much higher in Scotland than anywhere else in the UK:

If, as FM argues,

devolved policy is the reason 16-24 year old unemployment is falling more

rapidly in Scotland then it’s surely reasonable to assume that devolved policy

is miserably failing 16 & 17 year olds? Or maybe the experimental data are

not so credible after all?

To summarise, the ONS experimental LFS

data do indeed show a near one-third decline in Scottish youth unemployment

over the past year. However neither the APS or claimant count data provide

evidence to support the proposition that youth unemployment fell by a third. Rather, it seems there was indeed a reassuring fall in youth

unemployment but of a significantly smaller scale. If the experimental

data are credible then some serious questions need to be asked about what is

happening with 16 & 17 year olds and some immediate evaluation undertaken

to identify exactly what Scotland is doing with 18-24s that is so fabulously successful.

Of course, underemployment is also hitting young people particularly badly but that is a story for another day...

Update: 2100 9 May 2013

This blog was the subject of a short exchange today in Parliament between Ken Mackintosh, Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Angela Constance, Minister for Youth Employment. Here it is, Mr Mackintosh first:

To clarify:

- My only purpose in drawing attention to Scotland's very poor performance on 16 & 17 year olds on the experimental LFS data was to highlight the dubious nature of the series as a whole;

- it's not really a matter of 'the Scottish Government taking the credit when things go well etc' - it's about using statistics in a consistent fashion. If the experimental data are good enough to justify a claim that youth unemployment has fallen by a third, then we should be very worried about what they're telling us about 16 and 17 year olds. However, as should be clear to anyone who's read the blog, I think we should treat these data with extreme scepticism;

- I happily accept that the APS is a more reliable series. Again, one of my purposes in writing this blog was to make such a distinction between the experimental LFS data and the APS! What isn't credible is for the Scottish Government to use the experimental data to justify the one-third claim then argue that the sample size for 16 and 17 year olds is too small. Are we mean to accept that the sample size for 16-24 year olds yields a perfectly accurate result? That the experimental data are fine for 16-24s but we should turn to APS for the 16 and 17 year old cohort? Of course the LFS sample sizes are too small - this is why the data should not be used as the basis for such bold assertions.

In such a shaky economy, it is wise to inquire for an income protection quote for extra protection.

ReplyDelete